“Accessibility” doesn’t just apply to how buildings are designed, and it certainly isn’t about political correctness. In advancement offices worldwide, accessibility means that every constituent who wants to engage or interact with the office and personnel can do so.

There are two standards that advancement professionals need to be aware of when creating content online: Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 (the guidelines that define web accessibility) and Section 508 (an amendment to the U.S. Workforce Rehabilitation Act of 1973).

In our recent introductory post on giving and registration form accessibility, we explained that Section 508 requirements now mirror WCAG 2.0 recommendations — and this is a good thing for everyone.

To simplify things a bit for advancement purposes, there are four guiding principles to make all of your web content — forms included — accessible to everyone who wants to give to your institution online:

- Perceivable

- Operable

- Understandable

- Robust

The acronym commonly used for these principles, of course, is POUR.

We’re going to cover each of those principles in-depth in a series of four posts here on the Advance Prospects blog — starting today with “perceivable.”

By the end of this series, you’ll have a firm grasp of how to make sure every constituent can use your webpages and online forms, and every donor can give their gifts online with ease — even if those people have disabilities that make navigating the internet more challenging.

A Definition of the Perceivable Principle

For a web element to be considered perceivable, users must be able to perceive the information presented. In other words, it can’t be invisible to their available senses — it must be rendered in a visual, oral and/or tactile way.

Text is the most versatile way of presenting information, and it’s the cornerstone of this principle. Text can be presented and manipulated in multiple forms — for example, a blind person can understand a photo if the browser reads aloud the alt text, or a deaf person can understand an audio file if a text alternative is provided on the page.

Always Provide Text Alternatives for Non-text Content

Images, audio and video can add depth and interest to your webpages, and those media elements have been shown to improve visitor engagement. In the world of advancement, they can also lead to more donations and event participation.

But to people with certain disabilities, those media elements can make a webpage unusable.

Whenever you use a non-text element on a webpage, provide a text alternative.

- For images and video, make use of the alt tag. Describe the image or video in a way that will make sense of it for someone who can’t see it. Most content management systems allow you to adjust alt tags without touching any code.

- For audio and video files, provide a text transcript on the page.

By providing these text alternatives, assistive technology will be able to read the text aloud or convert it to braille.

There’s also an added bonus to providing text alternatives: Search engines will have an easier time understanding your webpages, which results in higher placement in search results.

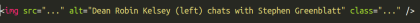

Here’s an example of an alt tag in use on the Harvard homepage. (To see this live, go to the site, right-click on the page, and select “View page source.”)

There is one web element, though, that continues to be a challenge for people with disabilities: CAPTCHA. While CAPTCHA systems are effective at combating spam, the visual version is challenging to see and interpret even for users with no disabilities. For users with certain disabilities, visual CAPTCHAs are completely unreadable.

To meet this challenge, the WCAG working group has required two different forms of CAPTCHA on a site that uses the technology. Typically, one form is visual and one is audio. This doesn’t completely eliminate the problem for some users, but it makes the CAPTCHA system usable by most people.

Provide Alternatives to Time-based Media

“Time-based media” is audio and/or video that may involve user interaction (in marketing terms, this is sometimes called interactive content).

- For prerecorded audio or video, provide an alternative form of content that provides the same information. For audio, this alternative form can be visual (as in video or images that convey the information clearly without sound), textual (as in a transcript) or both. For video, this can be audio, textual or both. WCAG 2.0 suggests that transcripts always be included when there is an audio element.

- For live audio and video, provide captions and/or sign language interpretation whenever possible.

- For video that has no sound, a text note should be included that says something like “There is no sound used in this clip.”

- If there is no transcript on the page, link to content that provides the same information.

- Always embed interactive elements (for example, links) in the alternative content.

The rule of thumb here is to provide the information in multiple formats to provide ease-of-use to the widest range of users.

Create Your Content With Different Presentations in Mind

People with disabilities navigate the web differently — which can make it hard for content managers to predict how their content will be displayed for every single user.

To put this in perspective, think about when you navigate to a website on your smartphone, and it’s displayed oddly because the site is not mobile friendly. The website was built with a desktop browser display in mind, but the mobile interface displays it differently.

The best thing you can do is to keep your content structure as simple as possible.

Expect that the content will be adapted to different presentation formats. A screen-reader will interpret the content differently than you might see it on your screen. Another example: While a sighted user navigates page content through visual cues (the size of a header, the introduction of bullet points, a background color that indicates items are grouped, etc.), a person with a visual impairment may rely more on text cues to navigate the page.

Here are a few things to think about when determining the structure of your page content:

- Make the reading and navigation order logical and intuitive.

- Ensure instructions are not dependent solely on visual or auditory cues — such as “Click the rectangle to continue,” or “When you hear the bell sound, you may proceed to the next page.”

- If the content cannot be rendered by assistive technology (such as interactive video content), realize that it will not be rendered at all for certain users. As we covered in the previous section, always provide alternative formats.

Make It as Easy as Possible to See and Hear Page Content

In addition to providing alternative content formats, you must make sure that the visual and audio formats are easy to perceive. Not all disabilities are all-encompassing. Visual impairment, for example, runs the gamut from complete blindness to red-green colorblindness to poor eyesight.

- Separate the background from the foreground. This applies to visual style (color) and audio content (clarity of voice).

- Use highly readable fonts.

- As a guideline, use 14 points as the minimum size for text in images.

- Call out links and controls with visual highlight.

- Avoid using images of text.

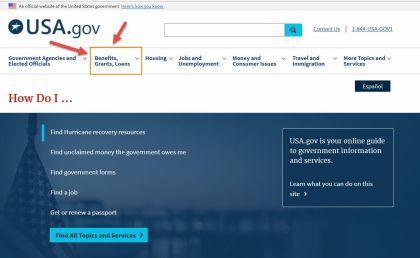

Try #4 for yourself: Go to USA.gov and use the tab key on your keyboard to navigate through the options. See how each selected item is highlighted in some way?

In fact, the USA.gov site is a great example overall of good accessibility practices in action. We encourage you to explore it.

Additional note: Color is an especially important page element to master for accessibility, since it can make or break the readability of your content. Ensure that color is not a key factor in understanding your page content. In other words, don’t convey information through color alone.

Are your web pages and forms perceivable?

The most important policy within the perceivable principle is this: Always provide alternative forms of information.

Some of your constituents may have disabilities that prevent them from using your website and online forms in the same ways you might be used to. To make web assets accessible, information should be laid out in a way that can be perceived in multiple ways.

Not sure where a webpage stands? Here’s a quick, free online evaluation tool you can use to check it.